Interview with Dr. Jeffrey Taylor on art business and forgeries

Dr. Taylor was one of the first professors who laid the foundation for the B.A. in Arts Management degree in International Business School, Budapest, Hungary – a partner of Oxford Brookes University, Oxford at that time. He inspired hundreds of students in pursuing an art business career. Curiosity and a certain degree of American attitude of saving the not yet so ‘known’ art – the Central European art; brought Dr. Taylor to Budapest, Hungary. It is also the art that brought him back to the USA. After more than four years, I met one of my first Arts Management mentors in the midst of the Armory Show.

Grosland Associate Director of the Masters in Gallery Management and Exhibits Specialization at Western State Colorado University, one of the 27 Certified Appraisers in Modernist and Impressionist Art, a Leon Levy Fellow; Dr. Jeff Taylor shares with us some intriguing information on art forgeries, appraising and research within the Central European and the American art markets.

Ruxanda Renita: This May, you took me through the backstage labyrinths of the Frick Collection. You have access to their library, which to art ‘freaks’ like us; it can get the pulse up in a fraction of a second. Is it the access to the Frick Collection that inspired you to become a Leon Levy Fellow? Could you tell us more about the fellowship?

Jeffrey Taylor: I’ve known the Frick Art Resource Library for quite a while, because it’s basically the best art research library in the world, especially if you’re looking for market information like auction and exhibition catalogues. They also have a research institute called the Center for the History of the Collecting that is doing some of the leading work on studying the art market and making that information digitally available to the public. The Leon Levy Fellowship is at the Center and I’m doing my research on Global Secessions at the Fin de siècle, which is when the monopoly salon system begins to break-down and secessions (alternative salons) begin to appear. This process takes places in Paris and then in Central European capitals (Munich, Vienna, Berlin… where the term Secession comes from), but this phenomenon also happened in Budapest, Prague, and New York. So I’m looking at the phenomenon of Secession as it happened across the Western art markets at this time.

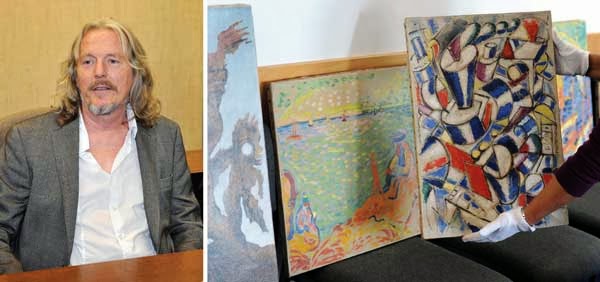

RR: Your perseverance inspired and still inspires myself and your rest of the students. In Budapest, you started art-forensics lab where Hungarian art and not only was ‘investigated’. Your project crossed the Atlantic and together with Prof. Stephen Cooke and Thiago Piwowarczyk you opened a lab at SUNY Purchase. The project caught not only the students’ interest, but also WSJ’s curiosity. What did it take to open a lab in the States and how would you describe the experience of working at the lab in Budapest versus NY?

JT: I realized back in 2007, when the so-called Pollock-Matters forgery case was going down that this art forensics stuff was going to be really important. So that’s when I got to know some people in Budapest who were doing this kind of work, and we began doing these services for the local Budapest market. The difference, I would say was that in Budapest, no one else, not the market, and not the museums, really understood what we were doing so there wasn’t really that peer-review rigor that you find in science in the US. At our lab at SUNY Purchase we really subscribe to scientific method. Stephen is a widely-published chemist, and Thiago is a criminal forensic scientist. Our work is transparent and reproducible, and we rely on published studies in conservation science to base our findings. We also aim to make these services affordable to collectors and the Trade so that the scourge of art forgery can be combatted.

RR: On June 7th, the first auction of Central and Eastern European (CEE) art is taking place at Sotheby’s London. Your PhD dissertation (and first book) was focused on CEE art and you lived and worked in the very center of the Central Europe – Budapest. Now, you are living in the biggest megalopolis of the world – NYC. How did you find the news of having Sotheby’s dedicating an auction entirely to CEE art? Is it surprising or as the Levine collectors said – ‘It is just about time’?

JT: It certainly is time. There’s always been this prejudice towards Eastern Europe (the Cold War distinction fades only slowly) that its art was never important. Just look at art history books from the 1960s, they don’t write anything about places East of Vienna…ever. It’s as if the Iron Curtain existed backwards in time. Back in my early years in the art business in Budapest in the early 2000s, I and some of my clients (NY and LA dealers) were quite sure that Hungarian cubo-futurist artist Hugó Scheiber or the avant-garde Béla Kádár would become big names in the international modernist canon… it didn’t happen. There’s a funny disconnect between, for example, those Hungarians who are in the international canon: Moholy-Nagy, Hantaï, Reigl, the architect Breuer, and, of course the photographers: Capa, Kertész, Brassaï…. And those who are in the Hungarian canon Rippl-Rónai, Csontváry, Ferenczy, Benczúr. A good example of the paradox is that the photographer Martin Munkácsi (who adopted his name in honor of the painter) is far more canonical in the West than the painter Mihály Munkácsy… who, art historians in Budapest note with black humor: “Munkácsy is world-famous to Hungarians.” Now that I’ve seen many parts of Central and Eastern Europe developing bold, self-confident contemporary scenes, I’m hoping we’re going to see the international break-through perhaps on the primary market.

RR: Which CEE artist from the auction or not is your favorite and why?

JT: Among those in the auction, I would say Attila Szűcs. I’ve been a fan of his for a long time. He is a true craft painter.