Ukraine at the 56th International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale

Author: Kinga Lendeczki

Published on: 18.07.2015

Ukraine is represented at the 56th Venice Biennale by the group exhibition Hope! showing works of young generation of Ukrainian artists: Yevgenia Belorusets, Nikita Kadan, Zhanna Kadyrova, Mykola Ridnyi & Serhiy Zhadan, Artem Volokitin, Anna Zvyagintseva and Open Group. The exhibition gives voice to personal hopes as well as critical opinion and reflections of artists on the present situation and future perspectives of Ukraine.

Kinga Lendeczki Before we start to talk about your participation at the Venice Biennale and the exhibition and its preparation, I would like to ask you to talk about those stages of your career, which you would regard as most important ones.

Anna Zvyagintseva I would mention one exhibition, which is strongly connected to my work The Cage, which is on view now in Venice. It was the exhibition Court Experimentorganized by curatorial union Hudrada. The project was realized in 2010 and I participated in it as a curator as well as an artist. Two members of Hudrada (Yevgenia Belorusets and Oleksandr Wolodarsky) and an ex-member of the group – Andriy Mochan, were prosecuted because of their protest actions. This show was our response to that prosecution. We tried to draw attention of the society on the problems of the corrupted judicial system in Ukraine.I would also mention my two solo shows. My first solo show entitled “Trusting movement” was summarizing what I am interested in as an artist. The second one “The radio behind the wall” was organized in January this year and it was an attempt to reflect on Maidan and on the war, which is going on in Ukraine.

N.K. For me those stages were the funding of R.E.P. collective in 2004, which still exists and I am a member of it and forming of Hudrada in 2008. Hudrada is publicly active since 2009 and we realized several projects together since that time. These exhibitions, such as the Court Experiment or the Labour Show, are part of our curatorial activity in which we started to create certain environments for ourselves. For a few years I was active member of artistic groups, but since 2009 I started to focus on realization of certain works, which I consider important for my practice, like Procedure room, Small house of giants or Babooshka. Ensuring mausoleum. From my previous exhibitions I would regard important the travelling exhibition The Desire for Freedom. Art in Europe Since 1945 organized by Deutsches Historisches Museum Berlin, RENDEZ-VOUS 13 in Musée d’art contemporain Lyon, The Ukrainians* in Daadgalerie in 2014 and from this year the Lest The Two Seas Meet in Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw and the exhibition Europe. The Future of History, which recently opened in Kunsthaus Zürich. In autumn I will exhibit at 14th Istanbul Biennial curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev.

K.L. At the 55th Venice Biennale you were one of the artists who participated in the exhibition Monument to a Monument, which was presented in the Ukrainian Pavilion. How does it feel like to represent your country for the second time in Venice?

Mykola Ridnyi Unfortunately the idea of the world without nations and borders seems to be more and more utopian in a context of recent changes in the world. In today’s Ukraine the idea of national state belongs to self-identification as a historical victim of Russian imperialism. But I do not appreciate romantic attitude to the idea of liberating nationalism because ongoing war as any war is not romantic. It doesn’t liberate civilians who live on lines of fire and who are similarly afraid of Russian artillery as of Ukrainian one. That is why the national representation of art is very problematic for me and being particularly in Ukrainian pavilion for second time is a big challenge which I accept to reflect on and criticize situation in and around my country with my works. The characters of the works which I presented in 2013 and which I present now are very different. In the case of “Monument to a Monument” I was talking about social and political tendencies which were not really discussed by the Ukrainian society, but which were very visible and problematic for me. One of the works the “Monument / Platforms” from 2011 was touching the issue of a demolition of a Soviet heritage in public space while the other one “Shelter” from 2013 was related to the topic of military education and conditions of bombproof shelters. Today it is visible that these issues have been grown from rare stories into problematic waves and they became anxiety points of public discussions. In a way before works were faster than reality, but today life is definitely faster than any kind of art. Mass media is extremely fast, especially with reports from the “hot spots”, and it is actually a big problem. The comprehension of the last events is missing. My aim connecting to the works which I present this year is not just to fix or focus on some problems, but also to try to open new layers of understanding and new levels of discussion.

K.L. In February was announced that the Pinchuk Art Centre would organize the exhibition at the Ukrainian national pavilion. What was the reaction of the local contemporary art scene?

M.R. I would rather like to answer from my individual point of view, because contemporary art scene in Ukraine is very segregated and doesn’t have one common voice or point of view. The organization of the show in the national pavilion is a state’s responsibility. In case of Ukraine responsibility is a shaky concept. Being more precise the pavilion depends on Ministry of Culture and on the policy of this institution. After the revolution of Maidan new people became part of the team of the Ministry, who had experiences in working in the field of contemporary art. They initiated the preparation of the Ukrainian pavilion for the 56th Venice Biennale, but then they were replaced by the new reactionary minister who supports now a conservative course focused on traditional values. After this change the main priority of the Ministry is to organize “patriotic” events and support soldiers in “anti-terrorist operation” with cultural initiatives. There is also a difficult economical situation now, when culture as institute is less important than other field of state policy in terms of war and crisis in the country. The only institution in Ukraine, which was ready to take responsibility for the pavilion and had a budget for this, was a private institution, the Pinchuk Art Centre. It is not so great situation when private sector has a monopoly for contemporary culture, but if the state doesn’t need it, there is no other choice.

N.K. When we speak about the critic of the local art scene, we also have to keep in mind that we don’t have professional critics on art. We have one magazine, which is extremely populist and oriented on a very ignorant audience. There are several efforts on publishing critics, but finally it is not working so actively.

Ukraine participation at the Venice Biennale is very important for the entire local scene. Since the first participation of Ukraine each time there are confrontations around participants of the pavilion. There is also no stable system for selecting the project. Nobody knows how will it work next time. In the case of the previous participation of Ukraine at 55th Venice Biennale, brilliant artists, like Zhanna Kadyrova and Mykola Ridnyi, who are also participants of this year’s show, were presented in the pavilion, but the state organized it as bad as it could be possible.

This year we wrote a letter to the Minister of Culture saying thank you to him and the ministry for their non-presence in Venice and non-participation in the organization of the pavilion. At the beginning after Maidan and after many things changed the new ministry invited two independent curators, Oksana Barshynova and Mikhail Rashkovetsky, who joined later to the curatorial group and worked together with Björn Geldhof. The ministry promised that they would support the renting of the pavilion and remunerate the work of the curators. But the ministry backed out from the project, they didn’t do anything for the pavilion except formally mentioning the commissioner. Curators invited by the ministry also left therefore all the project was given to private institution Pinchuk Art Centre and Björn as curator of the institution. I must say that here we get used to work with private institution and not with the state institution of Ukraine, because the cultural state institutions are dysfunctional. All these situations were quite tense for the whole local scene. It let off reasons to say something critical for everybody who wanted to do it. It was also very tense for us, and the project was realized in the atmosphere of internal confrontation of the cultural scene again.

K.L. The title of the exhibition, Hope! as well as the proposal expressed that the exhibition will voice the hopes of a young generation of artists for the future of Ukraine. What are your personal hopes?

M.R. It is difficult to talk about the future when there is a war in your country. The reality of today makes the most undifferentiated future. The war replaces future with projection of today-without-end, where the trauma became a new norm. It looks like for many people victory is more important than peace and nobody can imagine Ukraine after the war. What is important if it will be a country with a freedom of speech or repression of civil rights; country of social justice or neoliberal reforms; national and ethnic tolerance or hate? The future or futurelessness depends on the answers to these questions that are on responsibility of the society and the state.

A.Z. Part of the contemporary art scene was critical about the title of the exhibition, which they found problematic. Some were critical about the concept of the glass pavilion saying that it looks like a vitrine of a shopping mall. Björn proposed us to write down what hope means for us and several artists were also critical with this title. For example as I wrote in my text I would rather put a question mark after the title of the exhibition than an exclamation mark. Hope is transfer of responsibility to somewhere into the future. Not only the text – probably not everyone will read it – but also some of the works exhibited in the pavilion reflect on the title as well as on the transparency of the glass building.

N.K. I see that the word ‘critic’ is sometimes overused. You can name too many different things with this word. It creates a dramaturgy, when artists, who are participating in a show, are critical to the concept of the show. This way of criticality is included in the project and these lines of tensions create a more interesting internal structure. If you read the replies of other artists, you can see that everyone understands this category in a very different way.

K.L. What kind of influence did the Maidan have on you as an artist and on your artistic practice?

M.R. During the Maidan my activities as an artist and as a citizen were divided. I instrumentalized my artistic skills to activist need: drawing posters with social demands, organizing video screenings on a square etc. I didn’t see any sense to make art in that situation as a fast reaction on events and to present it in an art institution. Reflection and understanding of the situation requested more distance and time. Maidan not as physical phenomena, but as a media event created the opposite clichés such as “heroic revolution” or “armed coup”. Maidan was appropriated by the media war and by propaganda machine. In this context there is a big responsibility on art to create an alternative critical knowledge and provoke a discussion.

N.K. During Maidan it already became visible that certain forms of engaged activist art didn’t mean so much compared with the real mass protest. This protest had a strong experience, which could change your personality, but the effort of artistic representation, which was present there, seemed to be a kind of weak narcissism. I don’t mean the very practical things like posters or visual agitations produced by us, which had its certain role and meaning. I mean rather those individual artistic statements, which used Maidan as visually strong background. In my previous artistic practice, already before Maidan since 2012 I was interested in the idea of transformation of historical museum and expending somehow historical museum with the means of contemporary art and creating a certain kind of critical museum. I worked with political subject but through the medium of historical museum. That is why I was not interested in that activist or semi-activist forms of representation, but I was and I am still interested in how to tell the story of current transformation in Ukraine and the experience of catastrophe in a way, which really makes the viewer intellectually active.

A.Z. I madea solo show, “The radio behind the wall” in the beginning of this year, but I have to say that it was not anything like quick reaction from me. Except this show I did the series of photos of Maidan and of regular life going on in few steps away from it even in the most extreme moments. I have to say that many Ukrainian artists have this gap in their practice. They took some time to reflect on what happened without feeling obligatory to react immediately. I would say that Maidain influenced my work in a way that I became very attentive to words. Many artists and not-artists use images in their practices, we experience overproduction of images now and I try to be attentive to what I see and what I hear, to filter it and to make personal choices all the time. It is a kind of challenge for me and for many Ukrainian artists.

K.L. The 56th Venice Biennale entitled “All the World’s Futures” aims to emphasize the role of art in observing and reflecting the social and political changes of the world. In the international context of the biennale, where 89 participating countries represent the world, is it possible for the individual voices of the countries as well as the artists to be audible?

M.R. Participation in national representation of a country is a specific experience in the case of contemporary art, which basically uses an international language of expression and in a context where the world is becoming more and more globalized. The concept of national pavilions in Venice is old fashioned and even relict, but it is also very interesting in a way that from the exhibitions you can learn how the freedom of speech and democracy are developed in particular places of the world as well as to understand the economical conditions of the countries. Beside the artistic value it also has a sociological one.

N.K. In case of the Ukrainian pavilion the task to be visible was entirely completed. It is situated at a visible place in a visible form. There was a very strong support in working with mass media. The project was published through several channels and it had a plenty of guests. However to represent a country and to represent art are two very different tasks. In this case it was a political task to make visible to the world what is happening in Ukraine and at the same time present artists who deal with political issues and zone of catastrophe in their practice and whose practice is critically oriented on this topic. On the other hand artists, who are presented, get used to work with the organizer institution. We get used to work with Björn, he knows our practice very well and we know his way of curating. In this sense it was a certain kind of traditional partnership. During this show and now when I’m in Kiev I have a very strong feeling that it is almost impossible to say anything adequate about the show in a sense of a show of artworks which have texture, size, materiality. It is almost impossible to say something adequate without seeing it in reality. Maybe it has a sense to speak not about the show itself, but about the context of the show, the institutional background and the social situation, which this show creates. But the show itself is only there in Venice, only those ones who come and see this knitted cage of Anna, the big photographs of Yevgenia Belorusets looking through the glass to the street or see the brought things from the war zone in my vitrine, these people can experience the show. For all the others this show is rather a kind of social phenomena. I think it is also very interesting as social phenomena representing its time and its context. But it is a very different type of visibility.

A.Z. In your question you mentioned the main show curated by Okwui Enwezor. When I was walking in this show I had the feeling that it looks very chaotic, sometimes it was very hard to understand the connection of all the works. It looks like he gathered plenty of individual voices, mainly artists who reflect on what is happening in their countries. If you go deep in each work, most of them have they very strong voices and try to speak about very special situations. In our show there is similar curatorial attitude, but the small show is much more concentrated, it is easier to form an ensemble of individual voices there.

K.L. Could you tell us more about your work exhibited in the pavilion in Venice?

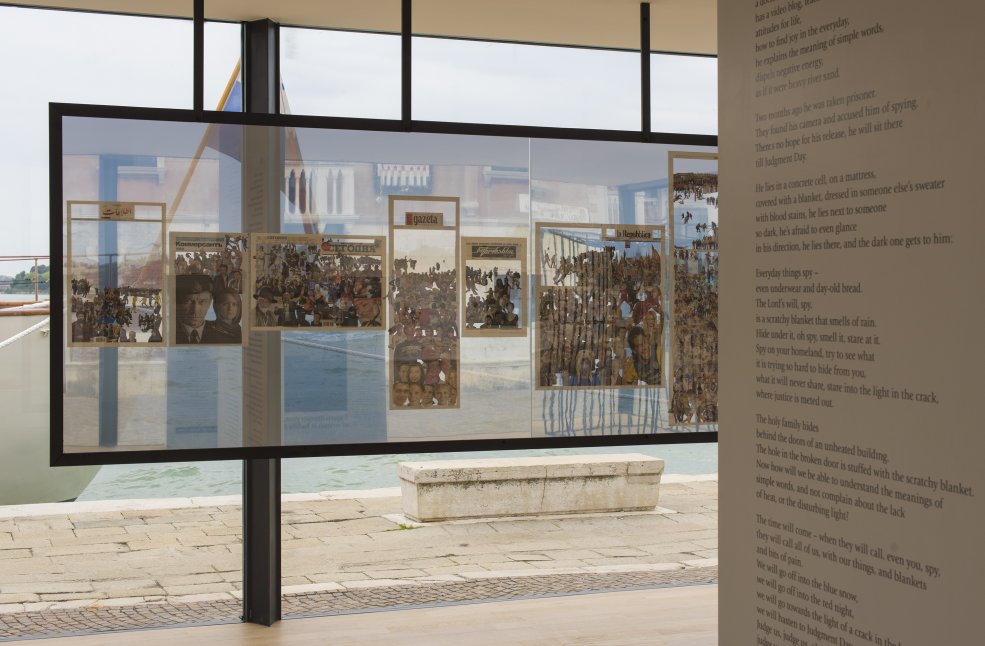

M.R. This year I was invited to two exhibitions in Venice: the Pavilion of Ukraine and the main exhibition “All the World’s Futures”curated by Okwui Enwezor. Most of the works are part of the “Blind Spot” project. It is a reflection on the war which is going on the east of Ukraine, but instead of focusing on the geopolitical issues of the conflict it concentrates on a problem of the reception and optics of society which follows and lives together with catastrophe. Selection of photographs documenting the conflict on Donbass connected with idea of a loss of vision. Photographs were sprayed with black ink and as a result of it a narrowing field of vision image is almost completely absorbed by black background. In the main exhibition this work is shown as a large series in combination with the other new work – video titled “Regular places”. This video touched the matter of hidden memory and echo of violence concentrated in public space. It was filmed in Kharkiv, the city where I’m based and which was lucky to avoid the war after period of very violent tensions.When I started to think about my work for the pavilion, a crucial point was the question of the distance between the place where I produce the message and the place this message is related to. In case of this situation this is the east of Ukraine. During the work I found an image of one building in Donetsk where there was a big glass window transformed into black holes after the attack. This defeat of transparency as a result of destruction of war is linked with an environment of the “glass pavilion”. It’s connected with relativity and precariousness of safety, which very depends on a context. The image combined with a text of a poetry of Ukrainian writer Serhiy Zhadan from the cycle “Why I am no longer on social media” representing the stories of the people whose life was directly interrupted by the war.

N.K. Through my work in this show at the biennale as well as my previous works like Limits of Responsibility I try to tell the experience of Maidan and of the war through the medium of historical museum. I already had this vector of interest before Maidan started and somehow it is possible for me to describe all of these situations through this vector. At the same time I see how morally problematic is usually the representation of catastrophe in place of comfort. When you show the heritage of war at the biennale in Venice where in the background you see beautiful white yachts parking in the lagoon, you understand this ethical tension. On one side you have burnt fragments of buildings and on the other side you see the yachts. It was very important for me to use this museum type of vitrine, which refers directly to Soviet type of museum. This vitrine is mediating between this image of catastrophe and the festival background of Venice.

A.Z. Maybe I was the only participant who had an old work in the exhibition. As I mentioned at the beginning, The Cage was made in 2010 for the exhibition Court Experiment. In our country and in other post-Soviet countries there is an iron cage in courtroom. If the person committed real crime, he or she will be in the cage during court sessions. If this person is not considered dangerous, he or she can just seat in front of this cage with the lawyer and the cage stands behind them like a ghost. The process often goes slowly, system makes everything not to let you leave and return to activist practice, some very simple process can last for years. Friends of prosecuted activist visit the sessions week by week, month by month. I made a knitted cage as a metaphor for this passing time and for certain comfort which one feels in the hands of justice together with feeling of own incapability to change anything.

Björn proposed me to present this work. I was thinking why not to make a new one, but at the same time I realized that this work still has a sense and maybe it has even more sense now. Probably you heard about those two Ukrainian citizens, the film director Oleh Sentsov and a military officer, Nadezhda Savchenko is in prison in Russia. For me it is important that this work is presented in Venice partly because of this situation. There are a lot of news and photos about these people and they are sitting actually in this cage.

K.L. What kind of the challenges did you have to face with during the preparation of the exhibition?

N.K. The preparation was very difficult. It was not a show in a palazzo, especially in a palazzo, which is prepared for exhibitions. It was a building just on the street and there were plenty of different challenges, several technical ones. It was one of the toughest exhibitions in our life, but finally it was done as it was planned and in this sense it was a strong organizer’s work. But in all the possible sense this show was not easy.

A.Z. Starting with the problems with the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine and ending with some technical problems, everywhere we faced with difficulties, but work is done and now it is time to reflect on what really has happened.